Switzerland wants a circular economy – but not to share products

Reuse, share, collect and recycle – in times of faltering supply chains, circular economies are in great demand. When products and materials circulate in closed material flows, it saves resources and avoids waste. Whether this succeeds also depends heavily on the attitudes and behaviour of consumers, who use, repair, buy second-hand or share products for as long as possible.

Political scientists from ETH Zurich, together with the Federal Office of the Environment (FOEN), have now examined how the Swiss people feel about the circular economy. Their representative survey of over 6,000 people shows that Swiss people think highly of the circular economy and are aware of its advantages, but rarely implement it in their everyday lives. “There is a clear gap between supporting it in principle and practical behaviours,” says ETH professor Thomas Bernauer, who led the study.

Majority in favour of support measures

According to the study, a clear majority of the population think that circular economy measures would have a beneficial effect on the Swiss economy. Those polled assume that the production of more durable products from more recycled materials will make Switzerland more competitive and less dependent on energy and raw material imports without affecting the labour market.

Accordingly, many respondents strongly support political measures that promote a circular economy, including a duty to repair for retailers, a repairability label, a mandatory declaration of air transport and service life, or a mandatory percentage of recycled material in packaging.

Prefer to buy new instead of sharing

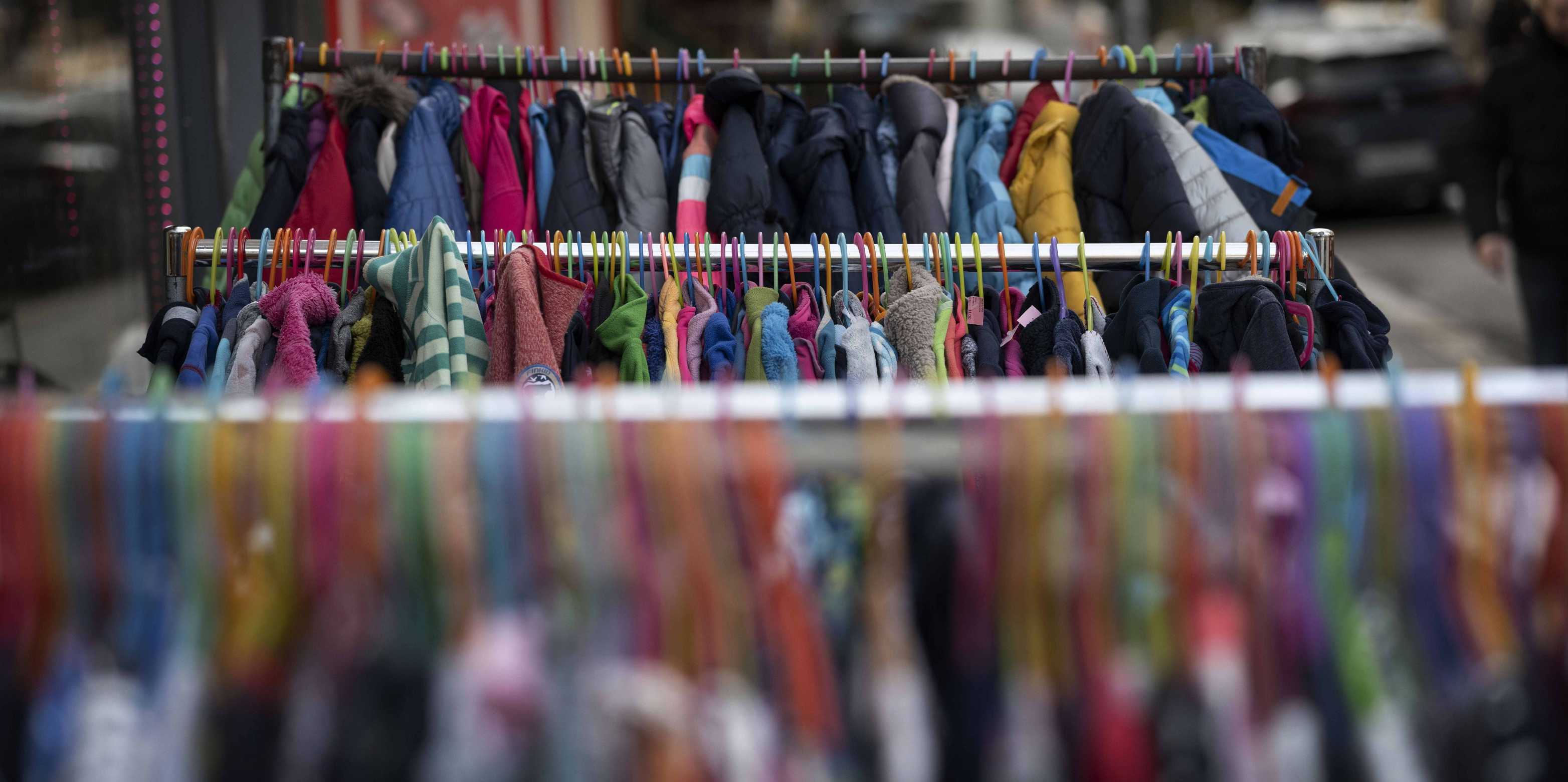

The majority of the respondents say that they are environmentally conscious. For the four products which the study considered in detail – smartphones, vacuum cleaners, washing machines and clothing – two thirds stated that they had sold or given away used products in the last 12 months. This shows that it is mainly clothing and smartphones that are given away second-hand.

In contrast, however, far fewer respondents were willing to purchase used products themselves. Thanks to charity shops and second-hand shops, a certain amount of second-hand clothes are purchased – but rarely vacuum cleaners, smartphones and washing machines. “There is a much greater inclination to sell or give away used items than there is to acquire them oneself,” says Franziska Quoss, project coordinator of Bernauer’s group. Supply and demand are thus in an unfavourable relationship.

The reasons for this, according to those polled, are that it doesn’t make financial sense for them to buy smartphones or clothing second-hand or have them repaired. They are also concerned about reduced quality in used goods. However, many simply state that they themselves prefer to buy and own new products.

Little inclination to share

Overall, the Swiss population displays weak circular behaviour. Whether clothing, mobile phones, drills or vacuum cleaners – Swiss consumers appear very reluctant to share consumer goods with other people, to rent, to get things repaired or to buy second-hand. “The frequently invoked sharing economy is still a long way off”, Bernauer comments.

Interestingly, this finding is relatively independent of how expensive certain goods are – even with cars and washing machines, renting and sharing play a lesser role. In the case of washing machines and cars, the discrepancy between supporting the idea in principle and practical implementation is somewhat smaller because these more expensive products are more likely to be repaired and recycled.

In addition, decision-making experiments in the study show that the willingness to pay for goods with circular benefits is quite limited. When purchasing a product, consumers focus much more on price and service life than characteristics like repairability or recyclability.

Room for manoeuvre for policymakers

Despite the sobering overall picture, the study also provides multiple starting points for policymakers. Governmental regulations such as a duty to repair for retailers, an obligation to declare the service life or a ban on unsold products have a good chance of having majority appeal.

“A repairability label that indicates how easy a product is to repair would, however, be of limited use, especially for inexpensive goods, if repairability per se is not a decisive factor in purchasing and purchased goods are rarely repaired,” Bernauer points out.

It would probably make more sense to strengthen the demand for used goods in a targeted way, for example through financial incentives and information campaigns to emphasise the advantages for one’s own wallet and the environment, adds Quoss.

In this way, the sharing economy could help to save resources and costs. However, its full potential can only be realised when sharing becomes chic and buying second-hand becomes cool.

More information:

Quoss F, Gomm S; Wäger P, Wehrli S, Amberg S, Linder J, Maissen P, Pahls H, Seidlmann E, Bernauer T (2023); Swiss Environmental Panel: Wave 8 Circular economy, ETH Zurich. DOI: external page10.3929/ethz-b-000590736

Source: https://ethz.ch

Published by CVTI